Stay Human.

A treatise on retaining your humanity amidst formidable temptations to surrender it.

My thinking on this topic has been somewhat chaotic; typically it begins with my gut reactions to the technological developments discussed below. This essay is an attempt to articulate clearly why I feel the way I do and what I believe that means for human beings individually.

Because of how my mind works, it takes me a long time to develop my thoughts clearly. There’s no way around that for me, unfortunately. So what follows is a living document. I anticipate continual updates and clarifications, and possibly exploring these concepts individually in new essays. The goal is for this document to serve as something of the foundation of my thought on this topic, representative of my approach to learning, thinking, and being in an age of ever-increasing mechanization.

For the time being, I hope what follows is both informative and useful to you. If you have thoughts, leave me a comment or email me directly. Your feedback may even make it into this document in future revisions.

The greatest challenge human beings face today is the threat of losing our humanity. At no point in human history has there been such a perfect conflagration of forces that work so well with one another to separate us from the fullness of human life. Maybe you disagree with that claim. Good. You should. In doing so you retain your humanity.

You know as well as I do that the last five years have seen profound changes in every aspect of human life: how we live, how we work, how we communicate, how we govern. I believe these changes—many of them forced upon us—have had the effect of altering how we perceive and participate in our cultures, nations, interactions with one another, the world around us, and ourselves. And I am convinced that these altered perceptions and modes of participation are in open war with our humanity.

The truth is that there is little we can do about it. There is no going back to a pre-COVID world and its assumptions, just as there is no going back to the days before social media or the internet or television or nuclear bombs. Nor do I think those days gone by could live up to the ideal we think they were. Hindsight shows that the pre-COVID days had a horde of their own problems that can only now be recognized with clarity. The silver lining is that pining for “the good old days” is deeply human, ingrained in our nature since our youngest days—even if it is misguided and strictly warned against:

Say not, "Why were the former days better than these?"

For it is not from wisdom that you ask this.1

Yet time—and the forces arrayed against us—march on. At the end of the day, neither you nor I can control where the world goes. “The earth is the LORD’s and the fullness thereof, the world and those who dwell therein.”2 God will judge righteously when the time is fulfilled; until then, you and I must live in the center of this maelstrom of forces that unrelentingly demand we capitulate our humanity. We only have one option.

Stay human.

I don't claim to know how to do this well. But I have a few ideas on how it can be done, and how you can keep your feet firmly planted against the tide.

Keep Your Head

If you can keep your head when all about you Are losing theirs and blaming it on you; If you can trust yourself when all men doubt you, But make allowance for their doubting too: If you can wait and not be tired by waiting, Or, being lied about, don't deal in lies, Or being hated don't give way to hating, And yet don't look too good, nor talk too wise; ...Yours is the Earth and everything that's in it, And which is more: you'll be a Man, my son!

—Rudyard Kipling, If

My company depends heavily on Google Ad campaigns to purchase targeted keywords. But recently we've had to make significant changes to our marketing strategy, as Google has been substantially increasing their ad campaign prices. This is not (strictly) inflation or price gouging; this is because Google search usage is plummeting. Users are increasingly turning to large language models for their search needs.

I have no doubt this trend is due to the ability of LLMs to collate and systematize information in a way that sounds like it makes sense. These models have been trained on astronomical amounts of data (made possible by the search engines they're slowly replacing); they're so effective that every major search engine is summarizing their own results with the assistance of LLMs.

This poses a problem: we don't immediately know if this information is trustworthy. Perhaps this is not an issue for some forms of information. That recipe for potato soup that ChatGPT put together for you will result in something tasty, something bland, or something in between (so long as it isn't hallucinating3). But if one depends on the results of these machines to serve as the foundation of *knowledge*, we must also be confident that the information corresponds to reality.

This is not a new problem. The entire industry of SEO optimization is about how to get content visible in the top search engine results. Whether the content is true is irrelevant. No doubt you've experienced this yourself: you search for a particular topic and click on a promising result, only to find an obscure blog article fluffed up with all the keywords related to your topic and with so many ads the page is nigh unusable.

Because the information retrieved by LLMs and search engines has the appearance of being grounded in a large body of facts, it’s far too tempting to trust the results. This is especially true if the results are just true enough to corroborate what one already knows, or if they concur with an idea or opinion one is inclined to agree with. And the honest truth is that it takes far more time, energy, and focus than most people possess to critically examine the results of these information-gathering machines.

This is why many people with the means to do so will buy multiple subscriptions to different LLMs and prompt the same information into each at the same time, cross-referencing each output. This, too, offers the promise of truth. We assess, make a judgement call based on what we know or believe, and add it to our storehouse of useful facts. Often enough it is functionally true.

Or is that just me?

The result is a stunted form of knowledge we’ve built through collection and compilation, by searching and snatching rather than questioning and examining, each piece of information a brick added to the defensive wall built around the ideas we want to be true. We get so used to the acquisition of bricks that we fail to stop and ask ourselves about them: “Are these the right bricks? Do I want to build an impenetrable wall around my ideas? Are these ideas the sort that I should be walling up to begin with?”

“All men by nature desire to know,” as Aristotle famously stated in the first line of his Metaphysics. Seeking, structuring, and ordering knowledge is human nature. It’s no surprise that the most significant technological leaps in human history have been knowledge-oriented: the printing press, the microchip, the internet. Despite my earlier gripes, I'm not against these things. There is nothing inherently wrong or evil about the existence of LLMs, search engines, or other such entities that collect and collate information.

But information is neither fact nor truth. It's a starting point. “There are four billion grains of sand in one cubic foot” may be true. Or it might not be. If one comes to learn this information via an LLM that collated it from multiple sources it found by scraping search engine results, then most people would be content with the LLM's response. It's good enough because it sounds right, and unless you're a geologist with a vested interest in the density of sand, you probably don’t need a more detailed answer.

Now imagine you make a habit of acquiring information this way, about any topic under the sun: Emperor Justinian’s legal reforms, effects of smallpox on Europeans vs. Native Americans, the origin of the Varangian Guard, the melting point of lead, a summary of Aquinas’ Ordo Amoris, nautical terminology for the different parts of a galleon. Most people don't have a vested interest in any particular one of these things, and LLMs are a perfect tool to get this information: it's going to be trained on more sources you'll ever be able to search in your lifetime, so its answers should be good enough. You ask, it responds, you collect, then carry on.

The cumulative effect of this habit is to come to the operating belief that most information conveyed by our collating tools, including that in which we have a vested interest, counts as knowledge. As generative AI gets better and better at producing mostly truthful responses to queries (and it is already very good), the temptation to become more comfortable with the LLM's answer will grow until we subconsciously come to accept that “good enough” knowledge is good enough.

Fight this temptation. Fight fight fight.

Acquisition of information is not the same thing as acquisition of knowledge. Knowledge requires us to be active. We must tune our faculties to investigation, forcing our minds to work differently than when we simply collect information. We must ask: “Is this true? What do I know about it? What can I be certain of? What am I missing?" When we do, we stop thinking of knowledge as pieces of information we can use.

Instead we begin thinking not just about the information, but about why we believe that information. We become the object of our study. We have think about our thoughts, assess how we know what we know, examine the ideas we possess and adjust those ideas based on the results of our investigation. We adjust the methods of our investigation—change our own minds—so that we can, ideally, change how we think in an effort to get closer to the truth. No other species possesses this ability; it is the inheritance of humanity.4

Attending to the way we think reveals to us the internal structure of our belief and how we form those beliefs. This is the foundation of the life of the mind. Anecdotally what I've found is that the more I investigate what I believe and why I believe it, the more often I ask myself, “Am I properly understanding mind external reality? Am I conforming my beliefs to what reality indicates?” So long as I can confidently answer yes—and presuming I’m being honest that I am accurately examining or understanding reality—the more confident I become in holding to my beliefs.

With confidence comes the ability for our beliefs to be challenged without us feeling threatened. Instead of our beliefs being like bricks in a defensive wall that strains when external forces hit it, they become something more like a mesh. Strong but flexible, connected but malleable, where reality can push against us but also break through. And because we are confident in our beliefs, we can be confident in the way we formed those beliefs. This makes us more capable of withstanding criticisms: to think about them honestly, not dismissively, and to weigh those criticisms against our beliefs such that we either adjust ourselves to reality, or rebut the criticisms clearly.

This is the essence of Kipling's admonition: “...keep your head when all about you are losing theirs and blaming it on you...trust yourself when all men doubt you, but make allowance for their doubting too.” This only happens when we’ve cultivated our minds with care. When we work to acquire knowledge. When we practice curiosity and careful thought, and don't settle for pieces of information that are “good enough.”

Stay human. Keep your head.

Invest In the Accidents

It is a good thing for a man to live in a family for the same reason that it is a good thing for a man to be besieged in a city...[or]...for a man to be snowed up in a street. They all force him to realize that life is not a thing from outside, but a thing from inside...It is, as the sentimentalists say, like a little kingdom, and, like most other little kingdoms, is generally in a state of something resembling anarchy...The men and women who, for good reasons and bad, revolt against the family, are, for good reasons and bad, simply revolting against mankind...Those who wish, rightly or wrongly, to step out of all this, do definitely wish to step into a narrower world. They are dismayed and terrified by the largeness and variety of the family...I do not say, for a moment, that the flight to this narrower life may not be the right thing for the individual, any more than I say the same thing about flight into a monastery. But I do say that anything is bad and artificial which tends to make these people succumb to the strange delusion that they are stepping into a world which is actually larger and more varied than their own. The best way that a man could test his readiness to encounter the common variety of mankind would be to climb down a chimney into any house at random, and get on as well as possible with the people inside. And that is essentially what each one of us did on the day that he was born.

—G.K. Chesterton, Heretics, ch. 14: “On Certain Modern Writers and the Institution of the Family”

When I was growing up my family would travel to Florida every summer for an annual family reunion. I’d be able to catch up with the extended family I never saw for the rest of the year: aunts, uncles, cousins, grandparents, great-grandparents, and even great aunts and second cousins. It was the only time our large family got together, as we were spread out all over the country: Florida, California, Missouri, and a handful of other states depending on who was moving around.

As I’ve gotten older I’ve come to realize that an intentional family gathering ritual is a rare experience for most people. I’ve known lots of people who lived away from their families, separated by distance or circumstance, who for varying reasons didn’t often gather as family in one place at one time. I’ve known several people who completely avoided their family because it was full of people they couldn’t stand. And believe me, I experienced plenty of family drama at those reunions.

But part of me wonders: was the drama more pronounced because of how rarely we got to see each other? What if we had to live close together? If we had no choice but to see one another every day or every week, if we had no choice but to participate in daily life together, would the drama have been there? Or would we have dealt with it?

What if we had to “get on as well as possible” with each other as part of our daily lives? Would things have turned out differently?

I’ve often wondered what communal life was like before the advent of the modern world. I certainly don’t have a framework to understand it: I was raised in the suburbs; my meals have, with rare exception, come entirely from grocery stores and restaurants; none of my gardening attempts have ever made it to maturity; the cities I’ve lived in span a total of 1600 miles. Our day and age is marked by fluidity incomprehensible to people in the pre-modern world. We can get any food we want almost any time from anywhere we like; we can live in one city while we work in another; entire families can be spread over a continent. Imagine trying to explain that to a tenth generation English farmer.

Conversely, I don’t think we moderns fully comprehend how different our world is from our ancestors. Imagine you were told tomorrow that you could never have a car again, that your current home was going to be your home for the rest of your life, and that you cannot travel anywhere without walking. That was already daily life for most of our ancestors. Imagine what that would do to your 10 minute drive to the grocery store or your 30 minute commute. It would change your world entirely.

When my wife told her European coworker that we were planning to drive 100 miles to visit my in-laws, her colleague was shocked to learn that it wasn’t even an overnight trip. A similar sentiment is captured in the adage, “The British think 100 miles is a long way, and Americans think 100 years is a long time.” But this European sentiment communicates a lost truth: our roots used to run deep in one place. Families, friends, and neighbors would have shared memories stretching further back than any one of them had been alive. Their world was smaller than ours: they had no control over where they lived, career options were limited (if there were options at all), and they married and formed families with people they (or their parents) knew.

Yet at the same time it was bigger. They were deeply entrenched in where they lived, because they had to be. They knew the land and the animals as well as they knew themselves, because it was required if they were going to survive with healthy animals and healthy crops. They had shared culture, religion, rituals, and feasts. And in some cases, even shared enemies.

This only worked because our ancestors learned how to get along with their shared community. There was a depth to their world that is hard to find today. It still exists, certainly, but it’s not the expected way of life. What’s expected is fluidity.

I think the best example of this is when one asks a teenager where they plan on going for college. We simply accept that if they’ve decided to leave their parents’ home—even if that’s the only home they’ve ever known—and move to some place across the country they have no attachment to or experience with, it’s a perfectly normal thing. For most of human history this would not have been normal. In some cases the idea of leaving your roots for a place you had no attachment to would have been nigh blasphemous.

Yet somehow this has become a rite of passage.

We make our friends; we make our enemies; but God makes our next-door neighbour. Hence he comes to us clad in all the careless terrors of nature; he is as strange as the stars, as reckless and indifferent as the rain. He is Man, the most terrible of the beasts. That is why the old religions and the old scriptural language showed so sharp a wisdom when they spoke, not of one’s duty towards humanity, but one’s duty towards one’s neighbour. The duty towards humanity may often take the form of some choice which is personal or even pleasurable. That duty may be a hobby; it may even be a dissipation...But we have to love our neighbour because he is there--a much more alarming reason for a much more serious operation. He is the sample of humanity which is actually given us. Precisely because he may be anybody he is everybody. He is a symbol because he is an accident.

—G.K. Chesterton, Heretics, ch. 14: “On Certain Modern Writers and the Institution of the Family”

Fluidity has replaced rootedness. We no longer think of ourselves as attached to a geographic place, even if we live in one location for an extended amount of time. Consequently it becomes easy to dismiss familiarity with the place we currently inhabit. Fluidity makes us glorified vagabonds, ready to uproot and drift to the next residence when the time or price is right, with little regret for what we leave behind. What’s worse, we lose familiarity with the people who live near us. We no longer feel a strong sense of community or solidarity with our neighbors.

I know this because I feel it. I know my neighbors on either side, but I can’t tell you the names of the people who live two doors down from me on either side. As for my next door neighbors, I interact with them fairly regularly—usually a nod or greeting when we see each other outside. Sometimes I’ll have an extended conversation with one of them. But when our interactions aren’t simply happenstance, they’re transactional. For example, when I needed to repair my fence, I explained to my neighbor who shared it the changes I was going to make (but since I was footing the bill—something of a point of contention—I didn’t leave it up for debate).

Contrast this with my book club. The guys in my book club live in my town, but not on my street. They’re nowhere near me; if I’m lucky, some of them live 15-20 minutes away by car. Most of them live at least half an hour away. Yet we stay connected through Discord and Signal. We talk every day. I know them better than my neighbors. I know their true beliefs and how they think better than I know my neighbors’ beliefs and thought processes.

But do I really know them better than my neighbors? I know a great deal of their unfiltered beliefs, but I don’t know what it’s like to live with them. I don’t know what it’s like to live on the same street. I don’t see them and their wives and kids. I don’t know any of that about my neighbors either, but there’s shared concerns we have that affect all of us in a way that doesn’t affect the guys in my book club. I should be invested in my neighbors. Yet the connectedness of the internet makes it feel like I know my online friends better than the people who live next door. The fact of the matter is, this is true. I do know them better than my neighbors.

There is something not right about this.

I’ve come to believe that the instantaneous communication offered by the internet and social media have, at best, stunted our ability to form, maintain, and hold relationships with our family and neighbors. At worst, it’s accelerated their erosion.

I don’t want to be misunderstood. I’m not saying the internet is a bad thing. I’m not saying social media is a bad thing, in theory. Yet what it’s proven to be—an instrument of extreme selection and manipulation—is a tool we can use to hand-pick which relationships are a part of our lives. It allows us to craft a bespoke circle of influence that reinforces our unfiltered sentiments.

For most of human history, people had no choice in who made up the individuals forming their behaviors and beliefs. They had to get along with each other because they were there; they needed each other because it was necessary for survival. People either got along cordially, became friends, or hated each others’ guts as enemies.

Yet they adapted to the reality of living with a wide variety of people whose presence was not a matter of choice. When you share a street, a city, the weather, or even the simple aspects of daily life, there’s a camaraderie that emerges precisely because you all share those things in common. It’s a feature of embodied life, a property that connections facilitated through the internet and social media cannot replicate.

The connectivity of the internet gives us a choice that human beings did not have a generation ago: the freedom to associate with whoever we like and abandon whoever we like. Even with technologies like the telephone this was not a choice people had; you couldn’t use it to hide. It was still necessary to get along with the people in your home and on your street.

But the instantaneous communication made possible by the internet and social media, facilitated through the smartphone, managed and directed by algorithms designed to hold your attention for as long as possible, has opened a way of building community that eliminates the need for embodied life. We can pick and choose who we engage with. We can filter for our preferred messages. We can expel, ignore, block, and report anyone who disagrees with us. We can do it for people we simply don’t like. It’s a mode of engagement human beings were not designed for.

When you’re forced to sit face to face with someone, to listen to them and understand them, you behave differently than if that person were a snarky post on X or wall of text on Reddit. You think differently. You speak differently. And your character changes accordingly. Is it any wonder that we seem to have lost the ability to debate? That we’ve lost the ability to be cordial? The facelessness of social media makes it tempting to remove the imago Dei from the way you interact with them. It becomes tempting to see them not as wrong, but as evil.

Fight this temptation. It dehumanizes others, and when you dehumanize them you dehumanize yourself.

Stay human. Love your family and neighbors. Invest in the accidents.

Abhor the Pill

I will not walk with your progressive apes, erect and sapient. Before them gapes the dark abyss to which their progress tends— if by God's mercy progress ever ends, and does not ceaselessly revolve the same unfruitful course with changing of a name. I will not treat your dusty path and flat, denoting this and that by this and that, your world immutable wherein no part the little maker has with maker's art. I bow not yet before the Iron Crown, nor cast my own small golden sceptre down.

—J.R.R. Tolkien, Mythopoeia

There is a sense of pride in being able to recognize the subtle style and techniques of an artist. This happens because artist puts himself into his work in a recognizable way, and it applies to any field we think of as art: painting, photography, illustration, writing, music, cinema, or sculpture.

Developing this ability requires us to take in multiple examples of an artist’s work. Starry Night and Wheat Fields with Crows tune our eyes to recognize van Gogh’s brushstrokes. David and Pietà help us recognize Michelangelo’s guiding hand in his chisel. The same sense of pride comes with recognizing how older works have influenced more recent artists. My daughter once told me about Dvořák; his Symphony No. 9 “From the New World” was clearly an influence on John Williams for the theme from Jaws.

But we recognize these because the products are the result of process. The artists who craft these things did not simply acquire their skill out of the blue; they learned their art, became competent in the craft, honed their abilities, and perfected their skill until they could repeatedly create the works they’re known for. The product would not exist without the process.

A work of art demonstrates the skill of the person who made it. In other words, art exemplifies style. This is why people like particular artists or storytellers. Individual styles are aesthetic “flavors” that emerge in the artist’s final product. Style is the end result of a competent artist employing the tools of their medium to achieve a desired form. Style is a necessary condition for a work to be considered art.

The greatest works of art demonstrate mastery—the highest form of competency—according to a style that makes them discernible from one another. There is a reason that “Return of the Prodigal Son”, “Pietà”, and “From the New World” are considered masterworks in their respective mediums. The artists that made them had an unparalleled grasp of their mediums, the tools available to them, and the forms they strove to achieve. Their prodigious skill in employing these components gave us the works we have today.

The Birth Control Pill was legalized in 1960 in the United States, and 1961 in Britain. It’s one of the most extraordinary inventions of the last century, but not in a positive way:

The Pill was the first transhumanist technology: it set out not to fix something that was wrong with ’normal’ human physiology--in the ameliorative sense of medicine up to that point--but instead it introduced a whole new paradigm. It set out to interrupt normal in the interests of individual freedom.5

The Pill made it possible to divorce the act of sexual intercourse from the effect of procreation in a way that no prior contraceptive technology was able to do. The result was the complete reorientation of thought around the sexual act in the Western mind. Only via this reorientation did everything afterward become possible: the “free love” movement of the 60’s, the SCOTUS ruling of Roe v. Wade in the 70’s, the increasing acceptance of gay rights through the 80’s and 90’s, and everything since--a trend exemplified by an ever-increasing acceptance has only seemed to become more depraved and transgressive.

This is the reason that, despite the inconsistencies and outright failings of its leadership over the last few decades, the Catholic Church’s prohibition of birth control is well-grounded. The reasoning, as I understand it, goes something like this:

God commanded Adam and Eve to “be fruitful and multiply.”6

God created sexual intercourse to be the means through which the end of fruitfulness was achieved.

Human beings do not have the right to make a means established by God an end in itself.

Therefore, obedience to God means that humans do not have a right to separate sexual intercourse from procreation by utilizing birth control.

I’m not Catholic, so I may be missing some of the details. But the logic is coherent. Even a staunch naturalistic atheist must admit that (2) is mostly true; he would reject the “God created” part of that premise but could not reject the fact that procreation only happens through sex.

The point here is not that I personally believe birth control is itself evil (though I think most forms are, but that’s another story). Rather, it’s that the human beings have always had to live with the reality that, when it comes to child bearing, means will always include the possibility of end.

Humans have always fought this. Abortion is not a new evil; as Rodney Stark points out in his book The Rise of Christianity, the Romans had extensive means of performing abortions7 and their laws and philosophers justified infanticide.8 Roman emperor Domitian ordered his Julia to have an abortion after he impregnated her. She died from the procedure,9 an all-too-common outcome.10 The early Christians abhorred the death of babies, born and unborn; their fertility rates outstripped the pagan Romans because they simply did not kill their children.11

The Pill—and the other contraceptive technologies since then—have enabled human beings to achieve that ancient dream of finally breaking apart the means and end of sex and procreation into separate ends in themselves. It interferes with normative biological processes to give us a sense of perceived control over something that was never designed to be separated.

It goes the other way as well: IVF treatments have enabled us to make procreation the end without the means of sexual intercourse. We can skip dealing with the troublesome bodies and their fertility issues; we can instead impose our will upon the sperm and egg and bring them together when and how we choose.

Dare I say this divorce of process and product, means and end, was never meant to be.

It is a human privilege and responsibility to create beauty. The first mandate that the man and woman are given together—“be fruitful and multiply”—is to create children (with God Himself doing the heavy lifting). Every parent has recognized at some point the inherent beauty of their newborn, despite sleepless nights of rocking colic-ridden babies. Yet the Pill interrupts this mandate by separating means and end. Development of reproductive technologies that interrupt it further (via processes like gene selection and artificial gestation) are accelerating. They will only exacerbate the problems that the Pill introduced.

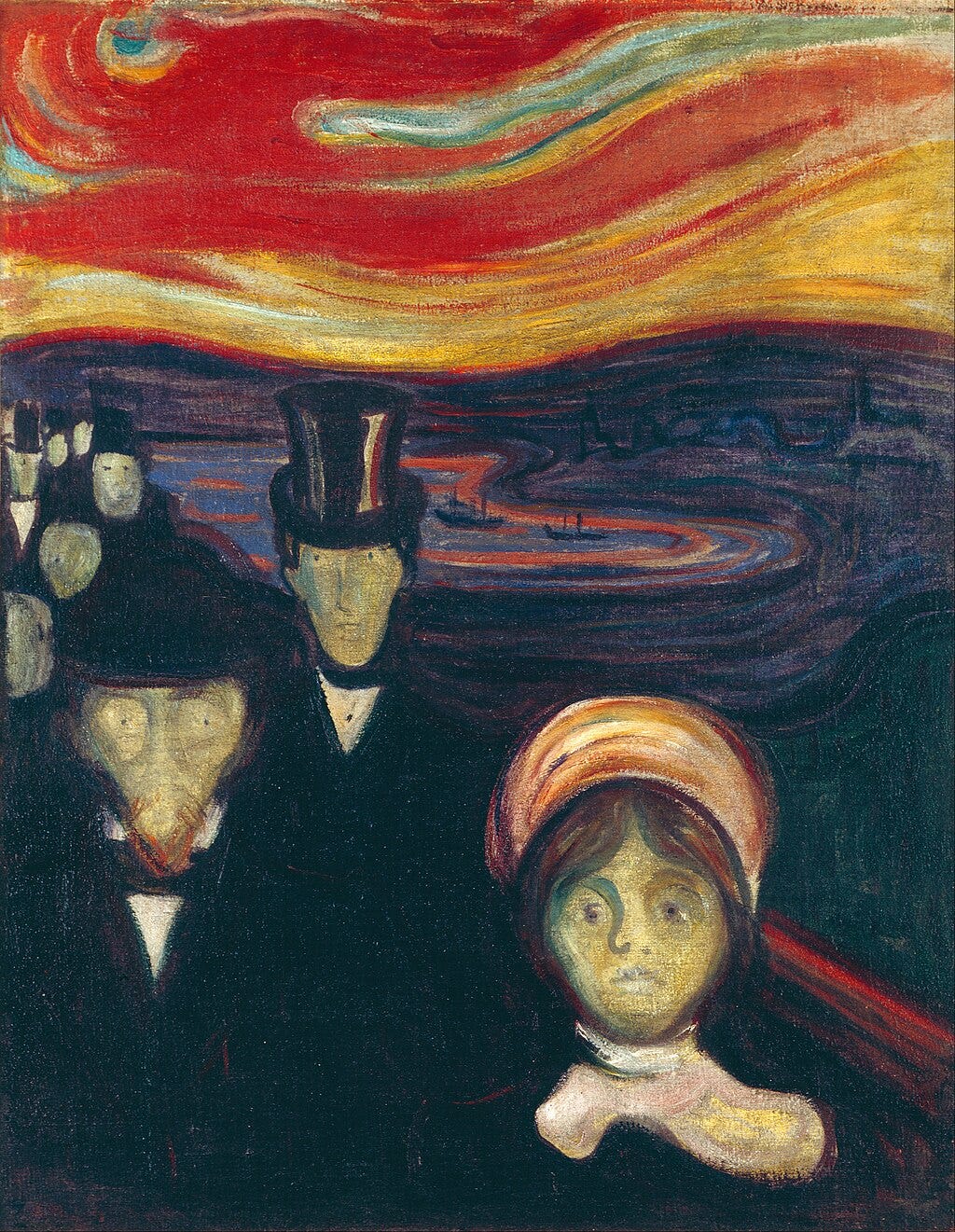

Obviously children are not the only beauty humans are capable of producing, though they are the most important. But we create beauty because it has been built into us: “So God created man in his own image; in the image of God he created him; male and female he created them.”12 We bear the image of a creator God who made the world in which we live—an enormous, terrifying, beautiful place. We are drawn to beauty, especially through art. It has a restorative effect on us, drawing us out of ourselves and grounding us in mind-external reality.

But a new Pill faces us today: Artificial Generative Intelligence. This is the Pill with respect to art. AGI, in a strange reversal of the Pill, removes the creative process and leaves us only with a created product. It severs the connective tissue of creative act between the artist and the work he creates. It separates the means from the end. Whether employed to generate imagery or text, the result is the same: we do not truly “make” the output.

We as humans are shaped and changed by the creative process itself. Even learning an artistic skill—drawing, painting, photography, writing—tune our senses to the aesthetics that resonate with us, aesthetics grounded in reality. But using AGI abandons this process for the sake of bringing about a product. We abdicate our responsibility to learn, to comprehend, to build, to become skilled in the craft of the thing. AGI tempts us to abdicate our responsibility to create well: we no longer wrestle with ourselves, our ideas, our skills, or the world around us. Instead we are reduced to engineers and pseudo-programmers figuring out the best way to manipulate the tool and craft the prompt to get the output we want.

The process threatens to become a feedback loop: AI models mine the internet for art and literature, but the more people use AGI to create their outputs, the more the models are trained on those outputs, and the more new outputs become some rehashed version of the earlier rehash. Eventually all outputs become simulacrum: they may look photorealistic or just like well-known styles or works, all the while discouraging people from developing their own style in favor of accepting the shortcut offered by the unidentifiable, mechanical, faceless machine.

We were not made for this. You were not made for this. Regardless of how frustrating it may be to feel stunted in your own skill—believe me, I wish I could draw well, but I can’t—you have a responsibility to cultivate it. You are a human being, different from the rest of creation; you are designed to create. Your ability to make, to craft, to be a “sub-creator, the refracted light”13 of God is divinely ordained. It is the “golden sceptre” you have been granted, because your exercise of that right has a transformative effect not only on the world, but also on you. Relinquishing that to a machine is surrender to the Iron Crown: it improves when you do not, parasitic upon your birthright, draining you of the will or motivation to become skilled in your craft, tempting you to forfeit the very image of God within yourself. As aptly expressed in the film O Brother, Where Art Thou?:

”Oh son...for that you traded your everlasting soul?”

”Well, I wasn’t using it!”

Stay human. Abhor the Pill.

Righting the Tilt

I want to make the point once again: I am not principally against the modern technologies that make all of these temptations so pronounced. LLMs and AGI do have positive uses—I use them every day in my job to speed up technical implementations. Social media—especially X and Substack—allows for the dissemination of information that doesn’t make it past the gatekeepers of outdated legacy media outlets. The internet has enabled an extraordinary amount of good.

It would be utterly foolish to think we could get rid of these technologies. They are extraordinarily powerful and extraordinarily lucrative. The world has been reshaped by them. We may as well try to go back to the days before the printing press. It won’t happen, and I am not certain it should.

So what is to be done about all of this?

The short answer: each of us have to make an intentional, determined effort to hold on to our humanity. There really is no easy path. It will take an extraordinary amount of self-discipline. You will need to impose this discipline upon your family. You will need to take ownership of your mind, your soul, your relationships. You will need to closely examine what you read and what you’re told. You’ll need to tear yourself away from the algorithms, turn off the black mirrored phone, and meet a friend for coffee. Do not abdicate your responsibility to think. Do not abdicate maintaining your relationships. Do not surrender your divinely ordained right to create.

Fight to hold on to your humanity. Stay human.

I know that sounds horribly abstract. But it isn’t. It starts small. Even one simple act that you can implement is a good place to start. Then work your way up to more.

Here are a few that might work for you. Some of these I do; some my friends do; some I aspire to do. Start with the one that is the easiest, and work your way up from there:

When you go to sleep, put your phone in the other room (get a dumb alarm clock if you have to).

If you work from home, put your phone in work mode and set it outside your work room.

Read to each of your children for 10 minutes at night (if you have a big family maybe start with 5 minutes).

Read the Bible with your entire family at night. Follow a “Bible through the Year” plan (or the Bible through multiple years).

Physically write all of your notes instead of typing them.

Get a comfortable pen and a notebook you like.

Take physical notes on things you’d normally be passive on: meetings, books, weekend plans, or anything else that requires structure.

Celebrate Christian feast days throughout the year, even if you’re not Catholic/Eastern Orthodox.

Light an Advent candle at Christmas.

Fast for Lent.

Celebrate Pentecost.

Read stories of the Christian saints together as a family, on their respective days.

Create your own family ritual that celebrates and recognizes the feast day.

Join a book club, writing club, or any other club dedicated to one of your interests.

Make sure your club meets in person regularly.

If you can’t find a club, create one. Use a tool like EventBrite to make it known.

Show up in person even if you’re the only one there.

Hand write thank-you notes after birthdays and Christmas.

Call your grandparents. Call your parents. Talk to them on the phone with your voice—not via text. Discern for yourself if FaceTime is appropriate.

Get a hard-wired phone for your house. Use your smartphone for emergencies or going out.

Find a book on an artistic skill you want to learn. Check it out from the library or buy it from the bookstore.

Get a dedicated notebook for the skill.

Spend 10-15 minutes every day on that skill. Make your way through each page of the book, even if it’s slow.

Buy and read physical books.

Mark up books with marginalia and highlights (but only if it’s yours).

Take notes on in your notebook if you’d rather not mark it up.

Avoid eBooks.

Buy art to hang in your home.

If you work in front of a computer, take a 10 minute break every hour. Go outside on your break.

Go hiking or camping.

Read old books: anything from before the 20th century.

Go to church.

Participate in a service project:

Sign up for one service project in your church.

Volunteer your time on a holiday, particularly around Thanksgiving or Christmas.

Exercise for at least 30 minutes three times a week.

You get the idea. Take this list, run with it, add to it, cross out what you don’t like. But use it to help cultivate your mind, improve your relationships, and develop your creativity. These things are your birthright, your gift, your responsibility. They are the things that make you human.

Stay human.

If you're not familiar with the term, "hallucinating" is when an LLM produces an output that appears coherent but is factually incorrect or outright nonsense—in other words, when it blatantly lies.

“Man has a rational principle, in addition \[to nature and habit], and man only.” Aristotle, Politics VII.13.1332b 5.

Mary Harrington, Transhumanism is Already Here.

Rodney Stark, The Rise of Christianity, HarperCollins, 1997, pp 119-121.

Ibid., pg 118.

Ibid., pg 121.

Ibid., pg 120.

“From the start, Christian doctrine absolutely prohibited abortion and infanticide, classifying both as murder...These views are repeated in the earliest Christian writing on the subject.”

J.R.R. Tolkien, Mythopoeia.